ESPN’s Chris Jones takes a turn remembering the good old days

Chris Jones, a very good writer, has a piece in ESPN The Magazine that argues, in the words of the subheadline, “Despite all the ways our favorite athletes reach out, we know less about them than ever.”

It’s a shorter version of the same argument Tim Keown made in his “Death of the interview” piece on ESPN.com yesterday, discussed in this B/R Blog post.

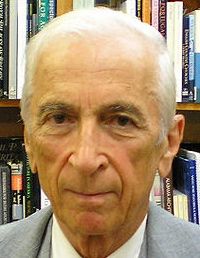

Jones tells the story of legendary New York Times writer Gay Talese tracking down a reluctant Joe DiMaggio at his San Francisco restaurant in 1966. During his career, sportswriters had built Joe into “an American icon.” Now, 15 years after DiMaggio’s retirement, Jones writes, Talese wrote a landmark piece that “stripped away the myths that had shrouded DiMaggio and showed him for what he really was: a sad, sometimes lonely man, now on an impossible quest for something like peace.”

Today, Jones argues, we’re regressing:

What’s strange, as well as alarming, is that we’re on the verge of a New Age of Hagiography. Despite all our advanced technologies and the seeming invasiveness of our coverage, or maybe because of those things, we actually know less about the real lives of athletes today than we have at any time since Talese walked into DiMaggio’s restaurant.

Sure, there’s Twitter, Jones writes, but: “It’s the pretty rare truth that can be crammed into 140 characters.”

On Saturday, Logan Morrison of the Miami Marlins tweeted 15 times, for a total of about 265 words. That’s not a huge amount of content. It’s roughly the number of words in this post so far. But how many words’ worth of insight did Joe DiMaggio give fans on any random December Saturday in 1939, when he, like Morrison today, was 24?

There may be a limit to how much truth can be crammed into 140 characters—hell, there’s a limit to how much truth can be crammed into a 20-volume encyclopedia—but there isn’t a limit to what you can learn from a limitless number of 140-character bursts. Twitter doesn’t block truth, and Morrison, like a lot of athletes, tweets every day.

Morrison also posted two photos. And from reading his timeline that day we might learn that he likes to joke around, he likes to joke around about bathrooms, and that he’s a big LSU football fan and he’s kind of combative about it. I don’t know if the tweet and photo about fishing with an escort is about fishing, a joke about escorts or a play on the name of his team, but I’ll bet someone who follows LoMo’s adventures more closely than I do got it.

Not exactly the foundation for a psychoanalysis of the Marlins’ left fielder, but it’s a lot more than nothing, and I dare say it’s a lot more than reading, second-hand, about how he was looking first-pitch fastball and just tried to get good wood on it.

“This isn’t a sports writer’s lament,” Jones writes. “It’s a fan’s lament. If you haven’t turned 40 yet, you’re further removed from the objects of your affection than you’ve ever been. Our modern walls allow something like Penn State to happen. They allow terrible secrets to be kept.”

Oh really? Twitter launched in 2006 and went mainstream, at least according to the Wall Street Journal, in 2008. The timeline of the Penn State scandal begins in 1998, when Jerry Sandusky was investigated by police and child welfare authorities for allegedly raping a child. There were more allegations in 2002.

The media missed it all. The “modern walls” had nothing to do with it. They didn’t even exist yet.

This is a common theme in laments for the loss of the old ways of journalism, remembering things being more rosy than they were. The watchdog media of days gone by, for instance, is missed terribly by people who seem to remember it doing a whole lot more watchdogging than it actually did. Here’s a Nieman Reports piece from 2001 talking about how the watchdog function of the press had fallen “into widespread disuse.” And that was before the U.S. media failed to call out the lies that preceded the Iraq War and missed the Wall Street fraud that caused an economic disaster.

I’m over 40, and I don’t remember this time when we knew so much more about athletes than we know now. I don’t remember anything like Brandon Phillips’ visit to a Little League game. You can dismiss that as a once-in-a-lifetime stunt, but you can’t deny that a kid tweeted at Phillips and the ballplayer responded with a nice gesture. That wasn’t happening in 1997.

I also don’t remember being able to find out who athletes are dating, and I couldn’t have been privy to what they were saying to the women they were hitting on, or what their junk looked like, even if I’d wanted to be.

And that’s just the nonsense. As baseball player and B/R Guest Columnist Dirk Hayhurst tweeted in response to yesterday’s B/R Blog post, “Twitter is a way to clarify intent amidst headlines.”

Athletes can speak directly to fans now, in a way they couldn’t before. Brandon Phillips has more than 177,000 followers. That readership would make him a decent-sized metropolitan newspaper. Does he manage his message sometimes? Of course he does. So did Joe DiMaggio, and most athletes in between. But at least now he’s not reliant on a third party to get that message—whether it’s a glimpse into his true personality or something else—to the fans, with all the distortion inherent in any game of telephone.

Hayhurst also wrote, “What am I more likely to believe: what a player says about himself in a tweet, or what a reporter *says* he says?”

That’s a lot of truth. And only 121 characters.

* * *

Talese photo: David Shankbone/Wikipedia Creative Commons. Morrison photo: Getty Images

-

Andy

-

Anonymous

-

Andy

-

Anonymous

-

Andy

-

Anonymous

-

Andy