How to write for casual fans and experts alike: Tell a good story

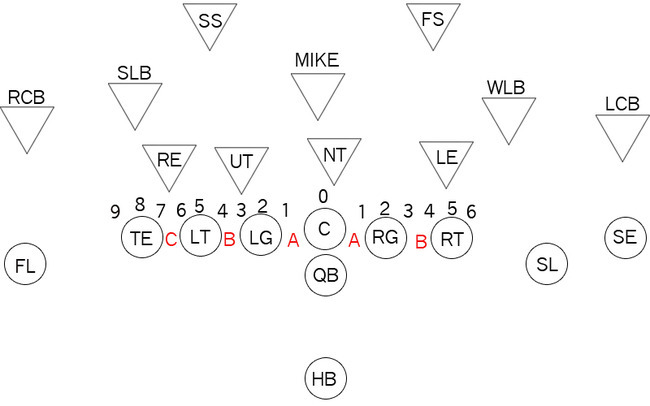

Sometimes, writing a good article feels like being a Ted linebacker tasked to twin the Mike on a double-A gap blitz when the nose tackle is inexplicably stunting toward the C gap and the offense’s I formation has a perfectly plotted gut run aiming the tailback’s first steps right toward the three-hole.

Got all of that? No? Well, welcome to one of the most difficult aspects of sportswriting: writing intelligent, engaging, thought-provoking material for the largest audience possible without sacrificing sport-specific expertise.

As sportswriters, one of the greatest challenges we face is making our work as meaningful as possible to as many people as possible. This challenge is amplified, of course, by the range of knowledge inherent in our audience.

Some readers are going to read through your average NFL article knowing exactly what the difference between a SAM and WILL linebacker is and wonder why you bothered to explain their roles in the first place. Others are going to feel their eyes glaze over at the very mention of quarters coverage or a designated Joker.

Our goal, then, is to make sure the casual fans get just as much out of our work as the hardcore fans, all while keeping the article accurate and showcasing our mastery of the subject matter.

So how are we expected to teach calculus to cave people?

Easy. You just tell them a good story.

That is, after all, what this comes down to. What sportswriting is all about. It’s how you learned to crunch numbers, probably, subtracting the three apples Annie ate from the six she started with. In this sense, the onus is not so much on clarifying terminology or refining playbook prose, but on simply telling a story people care about and using your extensive knowledge as a paintbrush to accentuate the larger literary strokes.

Every good analysis should tell a good story, and good stories should start with great leads.

You could have the market cornered on shotgun formations and not a single soul would care if he can’t get past the first paragraph. The first few grafs—heck, let’s just focus on the first graf—should be dynamic and to-the-point. No meandering, no finding a roundabout way to make your point while flaunting unnecessary professorly flourishes.

Just get to the point. Tell us why it matters, why we should care about it, why what you have to say is of any consequence. And then begin your analysis.

If we write with a story in mind, a clear direction of where we want the article to go, then the terminology just comes naturally. A strong narrative, something that really captures readers from the onset, will make everything else flow more organically, or from within the story itself.

Troublesome terms, the ones that may disengage certain readers when left on their lonesome, become secondary in the context of the narrative. They merely serve to support it, to clarify certain points and to offer helpful, descriptive details.

We don’t want to lose readers while ruminating on the merits of man vs. zone coverage, but we won’t if we’re sticking to a strong story and letting that tale do the legwork for us. Finding that story, plotting its direction and selling it from the first graf is a far more important challenge than negotiating the technical language within.

As writers, sometimes it’s worth taking a step back and asking what exactly we’re trying to accomplish in a given piece. When I read through film breakdowns, or what I like to term analytic narratives, I ask myself: Am I reading someone’s term paper, or am I reading someone’s thoughtful, nuanced, well-written story?

If it’s the former, I’m likely to shut off a certain switch in my head that allows me to follow the article to the extent I really should, and I’m guaranteed to get less out of the material than the author intended. But if it’s the latter, I can’t help following along.

I could be the world’s biggest soccer mom (note: I am not actually the world’s biggest soccer mom … I’m third at best), but I wouldn’t get hung up on X and Z receivers because the narrative would be my central focus.

Is the balance tricky? Yes. But too often, we get stuck in our own fog of self-assertion when it comes to declaring written expertise, and in the process, we sell our readers short. Because it’s not about making ourselves look smart or letting the rest of the world know we can break down film with the best of ‘em.

It’s about telling a good story, one where Ted and Mike are just characters.

-

Jim F

-

Anonymous

-

Jim F

-

Joshua Edwards

-

Joel C. Cordes