The Two Commandments: How to write about sports and religion

To find your journalistic bearings in the muddy mix of sports and religion, you would do well to read two recent articles that use the Super Bowl as a springboard to examine this (un?)holy alliance.

To find your journalistic bearings in the muddy mix of sports and religion, you would do well to read two recent articles that use the Super Bowl as a springboard to examine this (un?)holy alliance.

Mark Oppenheimer’s illuminating “In the Fields of the Lord” appears in the Feb. 4 Sports Illustrated (the story is behind the paywall online). With a Ph.D. in religious studies from Yale, Oppenheimer has the academic training to provide sophisticated analysis of the nuanced ways in which religion has appeared in the arenas of sports, and he has the wide-ranging journalistic experience to write with flare.

Michael Serazio is also an academic, but he explores a different angle on this topic: sports as religion. In his Atlantic piece “Just How Much is Sports Fandom Like Religion?” Serazio examines the analogous relationship between those two areas of high concern in American culture. He points to a French theorist who claimed that religion’s chief social function is to create and reinforce bonds in our society. Serazio argues that sports plays a similar role, and in comparable ways.

You don’t need to have undergone a lengthy and grueling intellectual regimen like Ph.D. studies to get your readers (atheists and believers alike) to say “Amen!” to your writing on sports and religion. Humility and intellectual curiosity—qualities that you can cultivate—will get you off to a strong start.

With even nascent growth in these two journalistic virtues you are more likely to fulfill the first commandment of writing about religion and sports:

1. Thou shalt not preach

Whether you are a fervent religious believer committed to witnessing to the exploits of your favorite God-fearing athlete or you are an atheist with an ax to grind against public religious displays on the court or field, being uncritical or too critical is bound to shrink your audience. Avoid anti-religious screeds and glowing athlete hagiographies.

When you read Oppenheimer’s and Serazio’s articles, you won’t find any glaring evidence of their personal views on religion. They seem to use an approach to writing about religion that I encourage my students to adopt when studying it in an academic setting, “methodological agnosticism.” An MA can be a committed atheist, a strong religious believer or anyone in between. They simply bracket their personal views on religion in order to restrict their coverage to what can be known about the subject using secular tools of inquiry.

A journalist covering sports and religion will not get far trying to deduce whether there is a sacred force at play on the field, or by taking great pains to dismiss such a notion. There is a lot more illuminating terrain to explore that can get the attention of a wide and diverse readership. Once you’ve considered what you can’t know about religion and sports using secular tools of inquiry, imagine all that you can access.

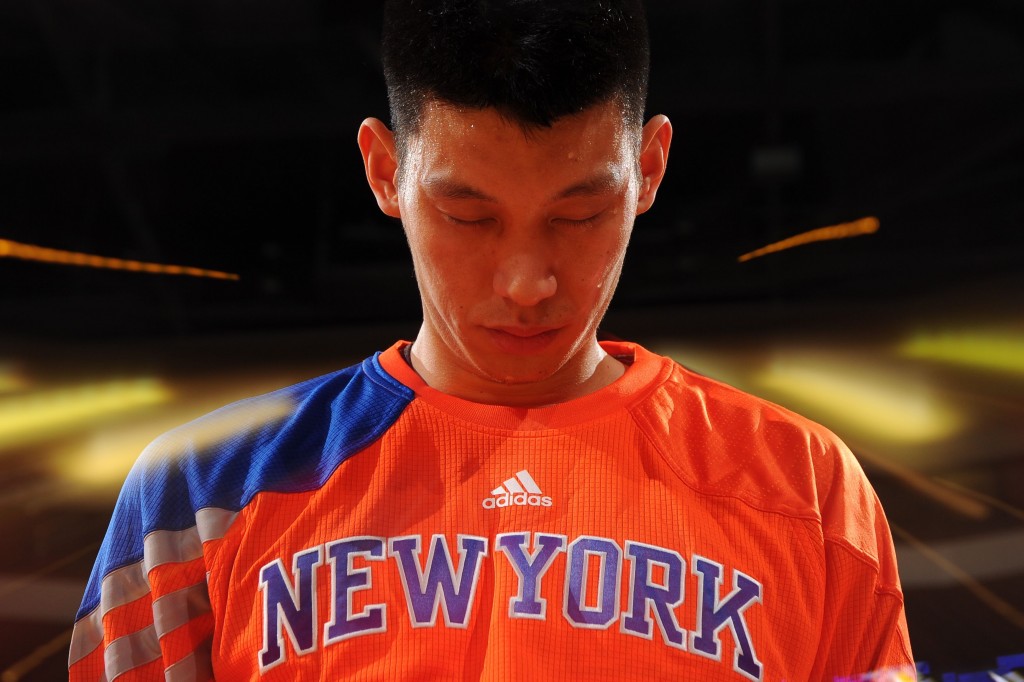

If, for example, you had scoured YouTube for information on Jeremy Lin after his breakout performance against the Nets last year, you might have found a clip of Lin’s “testimony” in church, in which he explains the various serendipitous events that led him to a professional basketball career. (And this was before the serendipity had reached “linsane” heights at MSG!)

You could have then written an eye-catching piece about how the breakout performance of this largely unknown point guard was the latest improbable turn of events for a religious athlete who had come to believe that a divine hand was scripting his dramatic basketball story. Few readers are interested in whether you believe such miraculous intervention is possible. They will be much more receptive to informative context you provide on how Lin’s beliefs influence his career choices (from his play, to his endorsements, to his altruistic endeavors off the court); which brings us to commandment number two.

2. Thou shalt read

You can avoid creating a hellish experience for your readers when writing about religion and sports by refusing to offer uninformed commentary on the subject.

Even if you have played basketball at multiple positions, you wouldn’t write an article on the Top 10 Ways the Lakers Can Make the Playoffs without having watched a game this season, or without having stayed attuned to the dynamic ways in which Kobe Bryant and Steve Nash are trying to adjust their styles for an underachieving team.

Likewise, just because you’ve been to synagogue, church or temple doesn’t mean you should just shoot from your holy rhetorical hip. To write compelling work on religion and sports, you should be aware of both diversity and dynamism in religion. Consider, for instance, how changing religious attitudes toward LGBT issues may create new spaces of inclusion for LGBT athletes. If you read broadly from both historical and contemporary perspectives, you will find fresh angles and compelling storylines.

For a through and meaty introduction to the topic of religion in sports, check out “Playing with God: Religion and Modern Sports” by William J. Baker.

For the sports-as-religion angle, you could read “Game Day and God: Football, Faith and Politics in the American South“ by Eric Bain-Selbo.

I have a ton of recommendations beyond these academic works (which include breezier, more journalistic books and articles), so feel free to email me at soneil1@utk.edu if you want other ideas for good reads on the subject.

Remember that when writing for B/R about the combination of sports and any other sensitive and controversial issue like race and gender (which, by the way, frequently intersect with religion as well), lean heavy on the sports end, and try to bounce your article off multiple editors (whether formal or informal) before publishing.

* * *

Sean S. O’Neil has a Ph.D. in religion from the University of Florida and he teaches American Studies, Religion and Sports, Latin American Religion, and Religious Social Ethics at the University of Tennessee. He has written about religion and sports in both journalistic and academic venues.

Jeremy Lin photo by Getty Images.

-

http://www.scardraft.com/ Scott Carasik