Blame hoaxers all you want, it’s the media’s job to get the facts

Is it unethical to pull a media hoax? Do hoaxers have any responsibility to let people in on the joke?

I got into an argument about that last week on Twitter, and while I find it an interesting question and don’t think the argument was won by either side, there’s one important takeaway for those of us in the media:

That argument doesn’t matter to what we do.

This is obviously a subject we think about a lot at Bleacher Report, because our writers spend a lot of time repeating information they’ve learned from various media sources, and verification and attribution are vital for us to get right. However much responsibility hoaxers carry in the eyes of society at large, we in the media have to be responsible for our own ethics.

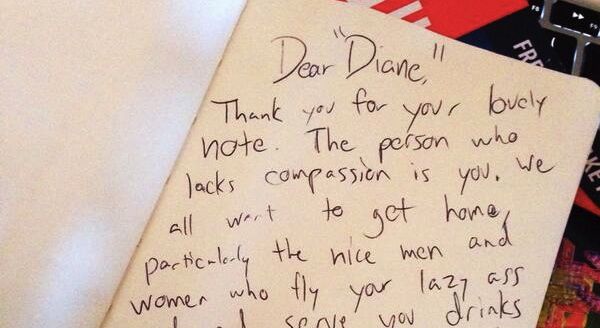

Here’s what happened: Elan Gale, a TV producer, live-tweeted a dispute he said he was having with “Diane,” a fellow passenger on a Thanksgiving Day flight. The in-flight battle, which involved Gale and “Diane” exchanging nasty notes and the woman eventually slapping him in the terminal, went viral, with several media outlets reporting it as true—including the New York Times, Mathew Imgram of GigaOm reports. Gale later revealed the hoax by tweeting a picture of a chair with the words “Here is Diana sitting in a chair.”

His next tweet: “Whoops. Meant Diane. Great time for a typo.” That’s a whole nother blog post.

Ingram, who covers media, wrote a piece headlined “Twitter hoaxes and the ethics of new media — what happens now that we are all journalists?” In it, he asked, “How much responsibility do the perpetrators of hoaxes bear for the perpetuation of untruths?” His conclusion:

The larger point is that we are all in this thing together now, this distributed and networked media ecosystem, and we should act like it. That means checking things before you retweet them, and not going off on witch hunts if you are on Reddit after a bombing, and other things as well. But blaming “the media” for getting it wrong is no solution either anymore. We are all the media.

On Twitter, I argued that “We are all the media,” while a handy catch phrase and even a useful way of thinking about things, is not strictly true. A better way to put it would be “We are all the media if we choose to be.”

That is, somebody pulling a prank on Twitter isn’t bound by any code of professional ethics that we in the journalism racket live by. We follow some of these rules—things like not reporting unverified rumors as fact—not because they are Platonic ideals but because they work for us. If you want someone to trust you to tell the truth tomorrow, tell them the truth today.

Obviously some ethical rules are matters of right and wrong. Ingram referenced Redditors falsely accusing an innocent person of being the Boston bomber. That sort of thing can cause real harm. But a silly joke is unlikely to cause harm. The only damaged parties in the Elan Gale affair were media outlets who took a well-deserved hit to their reputation because they did their jobs poorly.

If you’re a joker who doesn’t care if anyone believes what you say, then that guideline about telling the truth today so people will believe you tomorrow doesn’t do much for you. In the wake of the incident, Gale actively encouraged the world not to get its news from him.

By the way, I think I should mention that I didn’t defend Gale’s position because I thought his hoax about “Diane” was funny. As it happens I’ll forgive a lot if you’re funny, but in this case I disliked Gale’s joke.

Ingram and I passed part of a pleasant afternoon bickering about this stuff, with other smart people jumping in. I think you can get the gist of the argument at this link—until Gale himself jumps in and flies the conversation into a cliff of absurdity.

But whatever responsibility Gale does or doesn’t carry, the job for we the media is the same, and since this is me typing you know I’m about to invoke Lennay’s Law: Tell us what you know is true, and tell us how you know it.