There’s an interesting state-of-the-media conflict going on in Jackson, Miss.

In response to the Jackson State football program closing practices and not making players and assistant coaches available to the media for three weeks,

the Clarion-Ledger, a Gannett newspaper in Jackson, announced that it would “cease day-to-day beat coverage of Jackson State athletics until the situation can be resolved.”

In a statement published by the newspaper as an update to the story linked above, the university defended the right of coaches to decide to close practice, and said it had closed off media access to players and assistant coaches so the team could focus on adjusting to a coaching change. Head coach Harold Jackson was fired Oct. 6 and replaced by interim coach Derrick McCall, the only person in the program who has spoken to the media in recent weeks.

It’s unusual for this kind of conflict to blow up into a public announcement of the kind the Clarion-Ledger made. Disagreements over access are usually hashed out behind the scenes.

It’s also unusual for a football program that’s not a major power and the subject of intense media interest to restrict access. Jackson State is an FCS school—that stands for Football Championship Subdivision, and used to be known as Division I-AA—with a 1-5 record. They’ve drawn 24,457 fans to their two home games so far. Teams like that rarely try to dictate terms to the media. They’re usually happy with any coverage they get.

On the other hand, this column by Billy Watkins of the Clarion-Ledger illustrates why the newspaper takes access so seriously. Watkins laments the old days of unrestricted access to players and coaches, and writes that the people who lose out in the current atmosphere of limited availability are the fans of the team.

Watkins argues that Jackson State cutting off access completely makes a beat writer’s hard job all but impossible. He says he agrees with his paper’s decision to pull coverage, even though he wasn’t part of that decision.

Someone’s going to blink here, probably pretty soon, and it’ll probably be the university. A football program trying to put people in the stands wouldn’t seem to benefit much from alienating one of the biggest media outlets in town. But in the meantime, it’s an interesting test of where we are.

“Just how much is a paper’s coverage worth to a team,” asks Andrew Bucholtz on Awful Announcing, “and how much is covering the local team worth to a paper? We may soon find out.”

Bleacher Report has maintained a blacklist of clichés to avoid since 2012. The Quality Control team, using a combination of analytics and human judgment, has revised and expanded the list. These are the words and phrases that editors will zap from copy every time.

They’ll be on it like …

All right, we won’t do that thing of using a bunch of clichés in this blog post about clichés.

The numbers tell us that B/R writers have stopped using certain blacklisted items, like “when push comes to shove.” We’d like to think it’s because of writers diligently checking the list and absorbing its lessons. But we’re realists.

Still, the blacklist does an important job. Any B/R writer who knows it and avoids the words and phrases on it will not only save editors some work, they’ll write better copy. Any writer who becomes conscious of clichés and avoids them becomes a better writer.

Here’s is the new, expanded blacklist of 30 clichés for Bleacher Report writers to avoid:

Easier said than done

Time will tell

Back to the drawing board

On the same page

It is what it is

At the end of the day

To the next level

Step up

Without further ado

Drink the Kool-Aid

Jump on the bandwagon

Mail it in

One game at a time

Do or die

Back against the wall

Live and learn

First and foremost

Are you ready for some X

Tis the season

With [EVENT] in the books

Come back to haunt them

Throw under the bus

Tale of two halves

Taking his talents to

All is said and done

Any given Sunday

Right before our eyes

Send/sending a message

Will be interesting to see

Left in the tank

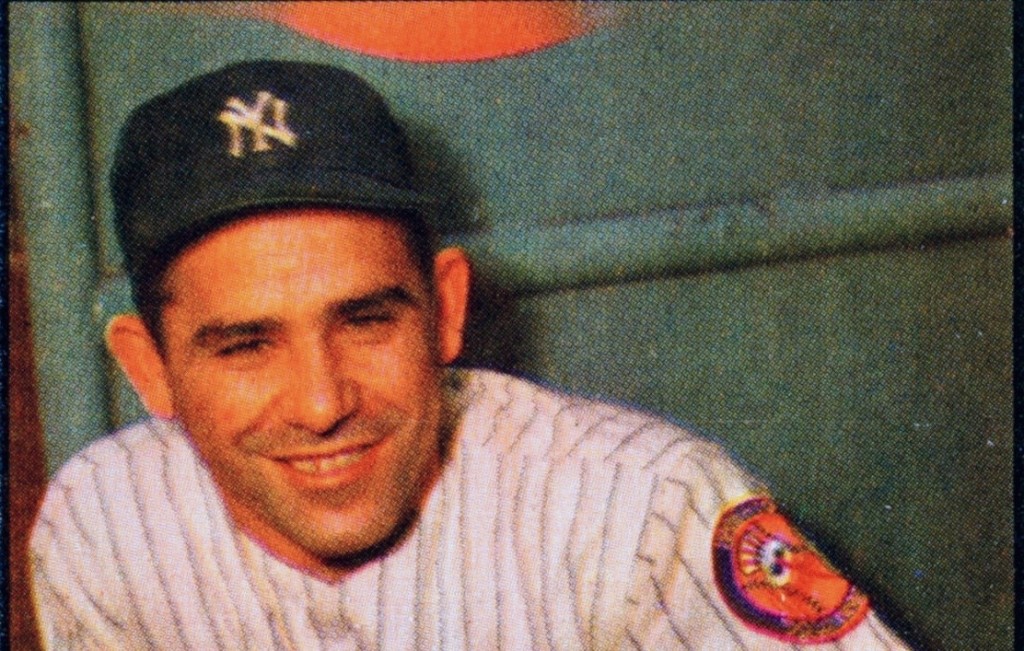

Yogi Berra said you could learn a lot by watching. You can also learn a lot by listening and reading.

Roy Peter Clark collected Eight language lessons from Yogi Berra at Poynter.org, and yes, those lessons come from some of Yogi’s malopropisms, which, Clark points out, often have a “stab of truth behind them.”

Sometimes the utterances of Berra, who died this week at 90, were just a little silly. “Nobody goes there anymore. It’s too crowded” is my favorite one of those. That’s more of an example of verbal sloppiness than folk wisdom. Berra obviously meant “Nobody I know goes there anymore.” But Clark digging into Yogi’s wit and wisdom shows how fruitful, and just plain interesting, it can be to examine someone’s words closely. An example:

“I’m as red as a sheet.” Yogi said this after he flubbed his movie line in a Cary Grant/Doris Day movie “That Touch of Mink.” Lesson: It always helps to tweak the predictable. Who would remember this if he said, “I’m red as a beet” or “white as a sheet.” So did the blood rush to his face or rush from his face? In essence, Yogi doubles-down on his embarrassment, reminding us that a mash-up need not be a mix-up.

That reminds me of one of my favorite phrases, which I heard as a kind of Yogi-ism years ago, though not from Yogi Berra. A customer at a shipping counter where I worked, a gregarious Irishman, meant to tell me that whatever choice I was offering him didn’t matter. Either was good.

“Ah, six o’ one, 12 o’ the other,” he said. Not only do I remember that phrase from a meaningless retail encounter decades ago, but I’ve used it myself ever since in place of the banal “Six of one, half a dozen of the other.” I love a nice tweaked cliché, don’t you?

Public domain photo via Wikipedia.

Michael Dunlap, who founded Hoops Habit and is senior content director at Fansided, asked a bunch of NBA writers for their best advice for aspiring sportswriters. You’ll probably learn as much by reading their answers as you’ll learn in a month in a college sportswriting class, so consider it a money and time saver.

If you’re in college, take statistics instead.

Zach Lowe of Grantland, Jody Genessy of Deseret News and Sam Amico of Fox Sports all say to read and write a lot, which is also common advice around here. They and others, including Sekou Smith of NBA.com and Fran Fraschilla of ESPN, talk about interviewing, breaking into the business, getting noticed, covering a team and quite a few other things.

The most important nugget, I think, comes from Ben Golliver of Sports Illustrated. “I think the most important question to ask is: What’s my competitive advantage?” he says. What can I do better than everyone else (or almost everyone else)?”

Noah Davis opens his piece about freelance writing at the Awl, headlined “If You Don’t Click on This Story, I Don’t Get Paid,” on an optimistic note.

“I have interviewed more than twenty writers, editors, media people, and journalism professors about the state of being a freelance writer in 2015,” he writes. “The general consensus is that it’s the best time since the very early days of the web to make money by writing online, and a marked improvement from even two years ago.”

The optimism doesn’t last, as Davis writes that the situation won’t last either:

The question is, how long will the relative good times of getting paid to write on the web last? Even venture dollars are exhaustible. While a few sites will probably survive, the existing (and future) business models can’t support all the ones that are currently vying for writers and eyeballs. “The people who make money off the internet are Facebook, Google, and Twitter and their billionaire executives,” David Samuels, a contributing editor at Harper’s and frequent contributor to the New Yorker, said.

Davis, whose similar story two years ago was headlined “I Was Paid $12.50 An Hour To Write This Story,” isn’t exactly accurate with his headline this time around. He reveals his negotiation with Awl co-editor Matt Buchanan: He asked for $350, and Buchanan countered with $250 plus $1 for every 1,000 page views, which Davis agreed to. “You have to bet on yourself,” he writes. “No one else will.”

He writes that he’ll update the story in a month with the totals.

The piece is worth the read for some wise words about how to survive as a freelancer, including advice that it’s sometimes better to take the quick assignment for a little money over the huge, time-consuming piece that brings in more money—but not enough more.

Nieman Reports has a report on the latest in robot journalism, which we’ve been following around here, in our analog way, for years.

Writer Jonathan Stray begins by talking about software agents that can monitor huge piles of information, such as open data created by modern cities or even countries. A bot can comb through crime reports for unusual trends that are worth coverage, but that a human reporter might not notice. Bots can spot patterns in market data that might reveal insider trading, Stray writes.

But there are also smaller, simpler bots that any journalist can use with no training, such as Google Alerts. Who hasn’t used that?

“We can expect to see much more sophisticated bots make their way into journalism in the next few years,” Stray writes:

This kind of artificial intelligence technology will be developed first for fields such as law, finance, and intelligence where there are large business opportunities. But consider what it could do for journalists. Imagine telling a newsroom AI to watch campaign finance disclosures, SEC filings, and media reports for suspicious business deals that could signal undue political influence. The goal is a system powerful enough to scrutinize every available open data feed, understand what each data point means in context by comparing it to databases of background knowledge and current events, and alert reporters when something looks fishy or interesting.

This kind of data mining is mostly used in sports for trivia, such as when Elias Sports Bureau or Stats LLC reveals that a certain pattern of events that just happened hadn’t happened since 19-dicketty-two. What are some more substantial ways we can put the bots to work for us?

This week’s SI Media Podcast with Richard Deitsch is worth a listen if you’re interested in how one of the biggest sports broadcasts in the U.S. comes together.

The guest is “NBC Sunday Night Football” coordinating producer Fred Gaudelli, who describes his role, in “football vernacular,” as being the head coach, with director Drew Esocoff as the quarterback. Gaudelli says he has about a dozen assistant “coaches” who are in charge of various things, such as graphics, editing or social media.

During the week, we set out a plan in all those areas in how we’re going to cover the game. And then when the game begins, my main job is to talk with Al and Cris and Michelle, and direct the editorial view of the game, while Drew is in there, like the quarterback, executing every play, every second of the game.

Al Michaels and Cris Collinsworth, the booth announcers, are also sort of like quarterbacks, Gaudelli says, because “it’s a real dance between who’s leading the telecast.” For the most part, he says, the announcers take the lead, but they and Gaudelli will discuss options during the commercials, with sideline reporter Michelle Tafoya sometimes chiming in. The football metaphor isn’t perfect.

Deitsch mentions at the end of the podcast that he found Gaudelli’s description of his week most interesting, as did I. Gaudelli patiently walks us through the week, day by day, describing the team’s preparation for the Sunday night game.

Also interesting: Gaudelli’s take on what went wrong when Dennis Miller was in the booth. Gaudelli didn’t hire Miller, but he has ideas about how it would go if he could try that gambit a second time, and speculates about the odds of an oddball hire like that happening again.

Molly Knight, author of one of the big baseball books of the year, “The Best Team Money Can Buy,” about the Los Angeles Dodgers of the last few years, wrote about how she got her start in the sportswriting business for espnW last week.

She writes that she came late to writing, having ditched the idea of med school and moved to New York to write at the age of 21. A few small breaks into her time there, she writes, she started getting “little freelance assignments” from a friend who had become an editor at ESPN the Magazine.

A top editor gave her an assignment to go into a major-league clubhouse, her first. “I learned later it was just a test to see if he would hear back from the public relations department about how I had made an ass of myself and the company,” she writes. “Literally, not making an ass of myself was the main assignment.” Here’s how that went:

The first professional athlete I ever tried to interview hit on me. He refused to answer any of my questions with anything other than, “What hotel are you staying in tonight?” That was the moment where I was sure I had made a mistake, and that the past three years of my life had been nothing but a series of mistakes.

My face turned every shade of maroon and I was so embarrassed it was hard to breathe. (The turtleneck probably didn’t help.) I assumed every day would be like this. What I didn’t know then was that I just happened to encounter the absolute worst sexual harasser on my very first day on the job. When he walked away to the training room, laughing about our encounter, one of his teammates apologized for his behavior and offered to do my silly quiz. I never forgot that kindness.

Knight, who covered baseball for ESPN the Magazine for eight years, writes that being a woman has its advantages on the beat, as players sometimes tell her things they wouldn’t feel comfortable saying to a man. The reverse is sometimes true as well, she writes, concluding, ” If I ran a newsroom, I would hire as many people from as many different walks of life as possible just to keep the perspective from getting stale.”

That issue of female sports reporters being sexually harassed, sometimes routinely, came up again over the weekend, when Minneapolis Star Tribune sportswriter Amelia Rayno wrote about her experience receiving inappropriate texts and touching from University of Minnesota athletic director Norwood Teague, who resigned suddenly Friday after similar sexual harassment complaints from two university employees.

Rayno’s colleague at the Star Tribune, Rachel Blount, tweeted that she’d had a similar experience with Norm Green, who owned the Minnesota North Stars—now the Dallas Stars—in the early ’90s.

Colleagues shrugged their shoulders or laughed. Like Amelia, I worried about losing access–or being taken off the beat. An awful situation.

— Rachel Blount (@BlountStrib) August 10, 2015

I hope our male colleagues understand: this is not funny. It's scary. It's horrifying. And women need your support to make it stop.

— Rachel Blount (@BlountStrib) August 10, 2015

Caleb Hannan, who wrote the controversial Grantland story Dr. V’s Magical Putter in January 2014, has spoken about it for the first time.

His big takeaway: He should have stopped and thought about what he was doing. That sounds obvious, and it might even sound like I’m being sarcastic by calling it “his big takeaway.” But it’s actually a hell of a takeaway.

“At every point, there was something more to investigate, something more to look into,” Hannan told Lauren Klinger at Poynter.org. “There was always this next thing to do rather than think about ‘Should I stop doing this?’”

I attended an ethics seminar for college journalists at the Poynter Institute in Florida in 1988, and the one lesson I remember from that week is that most ethical problems in journalism come not from journalists being evil or mean or greedy. They happen when journalists simply don’t stop, or even slow down, to think about the ethics of their story.

Here’s the background if you’re not familiar with the Dr. V story: Hannan had set out to tell the tale of a supposedly revolutionary putter invented by a mysterious woman named Essay Anne Vanderbilt, known as Dr. V. The inventor agreed to cooperate as long as the story was about the club, not her. Hannan agreed, but he learned that Vanderbilt had lied about her scientific credentials to investors, and that she was transgender, and he made her the center of his story.

Vanderbilt, who had attempted suicide in the past, begged him to stop reporting on her life, even telling him at one point that he was “about to commit a hate crime.” Eventually, before the story was published, she committed suicide. The story revealed her suicide only at the end. Speaking to Poynter, Hannan admitted his story treated Vanderbilt’s death “as an afterthought.”

I wrote two blog posts about the story a week or so after it was published. Though the story was initially praised on social media, outrage began to spread after a few days. By the time I read it and wrote the two posts, they were part of a massive online conversation around Hannan and the story that eventually came to include an editor’s letter by Bill Simmons and an examination of What Grantland Got Wrong by ESPN baseball writer Christina Kahrl, a trans woman.

Here are those two B/B Blog posts:

How to learn from the disaster of Grantland’s Dr. V story

15 editors and no one saw it: How the Dr. V mess is about diversity

Hannan appeared on a panel last week at a journalism conference in Texas, discussing what went wrong with his story, and then spoke to Klinger of Poynter. Klinger writes:

Hannan also said he was familiar with what it meant to be transgender but had not had enough experience with transgender people to know truly how it might feel to be outed. When other journalists call him for advice about writing about transgender people, which they do now, he redirects them.

“I say ‘I know someone at GLAAD you should talk to.’ I’m being glib, but that’s basically it. If they have specific questions, I try to answer them,” he said. “But I also reiterate that screwing up has not made me an expert and that they’d be better off talking to someone who is.”

I’ve invited Hannan to come on my SiriusXM Bleacher Report Radio show, “Content Is King,” to talk about the story and what he’s learned. I’ll update this paragraph if he responds.

Longtime Detroit Tigers beat writer Tom Gage will be honored as the Spink Award winner this weekend during Hall of Fame induction ceremonies in Cooperstown, N.Y.

I imagine it’s great for a writer to celebrate this award—the highest in the profession—with friends, family and co-workers, but Gage won’t be able to do that. At least not the last part. As noted in this interview with him in the Columbia Journalism Review, Gage left the Detroit News this spring when the paper pulled him off the Tigers beat after 36 years. He was hired by Fox Sports Detroit to write about the team, but the station laid off all its sportswriters in May.

In the bittersweet interview, Gage reflects on the changes in the business during his long career:

We used to fly with the team, and now for the most part, you never fly with them, you’re never on the bus with them, and you don’t stay in the same hotels. It used to be that if you had an issue you wanted to discuss, you could talk it over on the plane. I played many a card game with (former Tigers manager) Sparky Anderson, and it was in those games of Hearts that I could see how quick his mind was. Nowadays, it’s very difficult to get close to the team.

It used to be that you didn’t have to rush out of the press box to write everything up. But now, with the internet, it’s not like you have a 6:30pm deadline. Your deadline is all the time. You can’t linger in the clubhouse or wait until after batting practice to speak with a player a second time. There’s less time to develop your sources, your relationships with players, and to just build trust.

Gage cautions today’s baseball writers not to get caught up in statistics at the expense of storytelling. “I’m fascinated by numbers,” he says, “but they don’t appeal to the entire spectrum of baseball readers. I want to caution writers to not think that everyone is a hardcore baseball fan. You want everyone at the dinner table reading your story.”

You can hear the newspaper writer talking there: “You want everyone at the dinner table reading your story.” That’s certainly one approach—trying to appeal to as wide an audience as possible. It also may be the road to writing the same kinds of stories a lot of other people are writing.

One of the great things about this internet that’s admittedly made life a lot more miserable for beat writers is that there’s now room to write for just one person at that table who wants to go deeper than everybody else. However wide an audience you’re aiming for, I think that being unique is the best way to grab them.

Then again, they’re not giving me the Spink Award this weekend, so don’t dismiss the advice of the guy they are giving it to.